Split DNS for VPN in 2026: The Complete Guide to Security, Use Cases, and Step-by-Step Setup

Content of the article

- What split dns is and why it matters in 2026

- Split dns architecture: the building blocks

- Corporate use cases for split dns

- Security and privacy: keeping dns under control

- Step-by-step split dns setup for popular stacks

- Client platforms and policies

- Practical tips and checklists

- Real-world cases: what worked and what didn’t

- Common mistakes and how to fix them

- 2026 trends and what to adopt now

- Faq: the essentials

What Split DNS Is and Why It Matters in 2026

Basic Definition and a Simple Metaphor

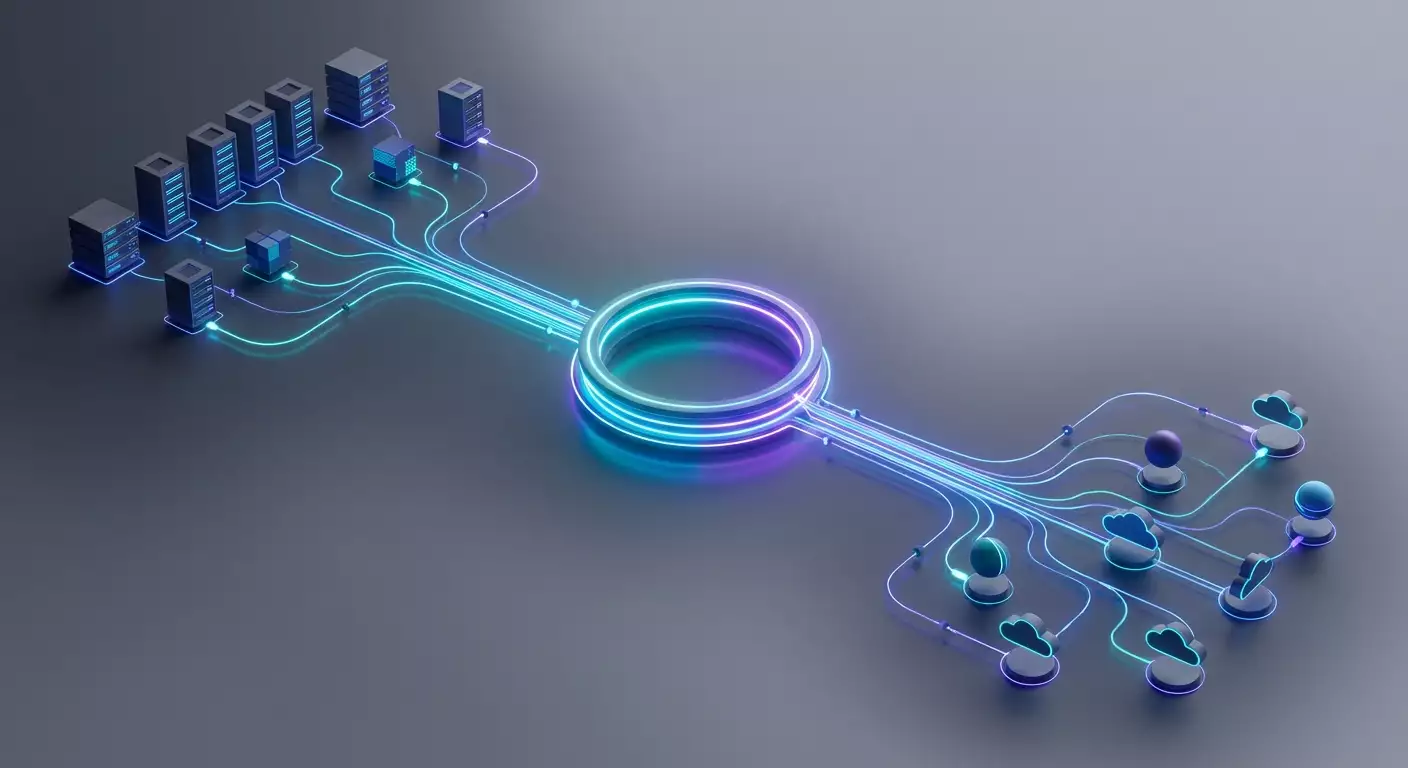

Split DNS is a strategy where different domains are resolved by different DNS servers, with query routing based on rules, VPN profiles, and client policies. Picture a doorman who only lets guests into the right areas: external domains go to public resolvers, while your company's internal names get routed to private corporate DNS servers. This neat separation minimizes leaks, speeds up resolution, and puts you in full control, enhancing security. It sounds straightforward, but as always, the devil’s in the details—and in 2026, those details have multiplied.

So why is this back in the spotlight? We’ve gone all-in on hybrid clouds, distributed offices, embraced Zero Trust, and added DoH, DoT, even DNS-over-QUIC. The old flat DNS just can’t keep up—it either reveals too much to the internet or breaks internal names. Split DNS offers the perfect middle ground. It’s like a traffic light at a complex intersection: the right lane, the right signal, ensuring no one cuts in line. Plus, it saves milliseconds or sometimes minutes when debugging complex resolution chains.

How Split DNS Works Hand-in-Hand with VPN

Through VPN, we build a secure tunnel. Then rules decide which domain resolves via corporate DNS, and which via public resolvers. Typically, conditional forwarding is set up with lists of zones like corp.local, int.company, or svc.cluster.local, directing queries to DNS servers on your office side or cloud hub. Everything else goes to the user’s ISP or a trusted managed DoH resolver you control.

Here’s a key point: the client’s behavior policy. Windows uses rule tables (NRPT), macOS and iOS rely on configuration profiles to route domains to specific resolvers, Android partially splits traffic with private DNS, and Linux with systemd-resolved manages routing by split domains. Bottom line: VPN doesn’t have to force all traffic through the tunnel—it selectively intercepts only the domains that need it. That’s what makes Split DNS great for performance and privacy.

How Split DNS Differs from Split Tunneling

This is a common confusion. Split Tunneling divides traffic by subnet or app, letting some bypass the VPN. Split DNS, however, only splits domain name resolution; routing of that traffic can be full tunnel, split, or any mix. You might have a full VPN tunnel for security but resolve external domains via public DoH, or split traffic but force all DNS queries through corporate resolvers. They’re independent mechanisms, though often used together.

Why does this matter? Because it lets you finely tune balance. Want fewer risks of internal names leaking? Resolve them only through internal DNS, while external domains go via DoH inside the tunnel. Want faster access to YouTube or CDNs? Let external domains resolve closest to the user, keeping sensitive stuff strictly internal. The flexibility is huge and can cut response times by tens of percent.

When You Don't Need Split DNS

If you have no internal domains, no private zones, and no difference between inside and outside names, then Split DNS probably isn’t worth the hassle. This is rare but happens with small teams fully on SaaS platforms and no internal servers. Another example is isolated thin clients with no internet access—there's no name separation to manage.

But in most real organizations in 2026, internal names exist. Think Active Directory, Kubernetes services, VPC and VNet private zones, private APIs, internal portals, service discovery via Consul or Istio. Wherever internal zones exist, Split DNS helps by reducing accidental external resolutions, protecting privacy, and delivering a seamless user experience—everything works invisibly without messy hosts file tweaks.

Split DNS Architecture: The Building Blocks

Roles of DNS Servers: Internal, External, and Recursive

The Split DNS setup always has at least two types of resolvers: internal ones authoritative for private zones (often recursive for internal hosts), and external ones that are public recursive resolvers or authoritative for your public zones. Sometimes a third layer appears—edge resolvers in the cloud acting as caches and distributors. This tiered approach cuts latency and reduces backbone load.

Internal DNS servers know your private zones like corp.local, priv.company, internal.zone, svc.cluster.local. Public resolvers know nothing about these and shouldn’t. Recursors cache queries, authoritative servers provide final answers. Clear separation is critical: keep private zones inside and prevent accidental exposure outside. This ensures clean pathways, predictable behavior, and control.

Zones, Conditional Forwarding, Stub, and Forward Zones

Conditional Forwarding is classic Split DNS—it lets you specify that queries for, say, .corp.local go to 10.10.10.10 and 10.10.10.11. Forward zones work great when integrating business units or during M&A: different teams manage zones but unified policy routes requests correctly. Stub zones simplify delegation—you don’t copy records, you just point to the authoritative source and resolvers know where to go.

Why is this convenient? It avoids duplication and desync risks from copying records. In 2026, most corporate DNS solutions handle forward, stub, and hybrid modes easily. Plus, you can layer on RPZ filtering to block malicious content and risky domains at the edge without touching internal zones. The end result is a logical, manageable path for each domain.

Client Resolver: Order, Cache, and TTL

The client is the little conductor. It decides which resolver to ask first, how to respect TTLs, and how long to cache. Windows controls this via NRPT and interface priorities. macOS/iOS use config profiles with DNS servers and domain lists. Android has private DNS policies and sometimes MDM app control. Linux uses systemd-resolved to route by domain and interface—an ideal friend to Split DNS.

Caching is crucial. You don’t want to query the cloud every minute for the same A record. But TTLs can’t be too long—long TTLs break service updates and migrations. A sensible 2026 TTL for dynamic internal services is 30–300 seconds; for stable ones, 15–60 minutes. This balances load and agility. Also enable negative caching to avoid repeated NXDOMAIN flood.

Encrypted DNS: DoH, DoT, and DNS-over-QUIC

DNS encryption is now standard with DoH, DoT, and DNS-over-QUIC protecting against snooping and tampering. But since VPNs already encrypt traffic, do you need double encryption? Sometimes yes. It protects against DNS spoofing on the user’s local network before hitting the tunnel, or enforces that external domains resolve only via trusted DoH even when VPN’s active. In these cases, enable DoH on the client and set rules carefully to keep internal domains inside.

The key is to avoid conflicts. Forcing DoH on all queries may prevent seeing private zones. The fix? A Split DNS policy that specifies internal domains go to corporate resolvers inside the tunnel, external queries go over DoH to approved providers. In 2026, many MDM systems and VPN apps support this natively—you just need to set the rules thoughtfully.

Corporate Use Cases for Split DNS

Active Directory and Internal Zones

If you use Active Directory, Split DNS is practically essential. Domains like corp.local or ad.company.internal must resolve strictly on domain controllers or trusted internal servers. Why? SRV and LDAP records are critical for login, GPOs, and services. Accidentally routing these outside leads to a flood of support tickets and sleepless nights. Split DNS ensures AD queries stay internal and safeguards against surprises.

Plus, AD needs accuracy: PTR records, proper CNAMEs, correct GC and site info. DNS separation simplifies troubleshooting—you can see exactly which servers manage the internal zone and check replication separately. That saves hours or even days hunting errors, especially with remote work and hybrid connections.

Hybrid Multi-Cloud Environments

AWS, Azure, GCP, plus on-prem—that’s the 2026 norm. Each platform keeps private zones or integrates with local DNS. Split DNS transparently routes queries: AWS services resolve through Route 53 Private Hosted Zone, Azure services via Private DNS, local systems through BIND or Windows DNS. Users don’t notice; admins manage all from one policy console.

Add Kubernetes to the mix. Internal names like svc.cluster.local must resolve strictly inside the cluster or via a corporate resolver that knows how to route to CoreDNS. Conditional forwarders link these worlds. This is crucial with service meshes and cross-cluster communication. Without Split DNS, you risk unpredictable timeouts and resolution loops. With it, you get clear direction and reliable behavior.

Separation by Business Unit and Mergers & Acquisitions

When one company buys another, name and zone clashes are the first hurdle. Both sides have internal.local, mail.internal, api.int, plus legacy leftovers. Split DNS with forward and stub zones softens the transition. You delegate zones temporarily, align policies, and gradually unify naming schemes. Users don’t realize two worlds coexist behind the scenes because their resolver follows consistent rules.

Even within one group, splitting helps. Banking security teams manage their zones and RPZ filtering; R&D uses experimental zones with short TTLs. Split DNS sets the rails without slowing local teams down—a vital balance of control and speed. The faster the business moves, the more essential flexible edge configurations become, rather than a monolithic setup.

Remote Offices, SD-WAN, and SASE

Branches operate via SD-WAN and SASE; users on the road connect over LTE. Split DNS lets you specify resolvers per scenario. In branches, use local caches and forward to hubs. For mobile users, a client agent knows what domains go through the tunnel and what resolves locally via DoH. Offline? Cache and negative cache keep things ticking until connectivity returns.

In SASE architectures, the resolver acts like a policy controller—checking domain categories, risk tags, threat status, then deciding to allow, redirect, or block requests. Split DNS works as a map: which domains are trusted, which only route in the tunnel, and which quarantine. All this happens without disrupting user habits—they type addresses, click links, and the system silently picks the right path.

Security and Privacy: Keeping DNS Under Control

DNS Leaks: How to Detect and Fix Them

A DNS leak occurs when requests for internal or sensitive external domains go where they shouldn’t—say, outside the VPN or to a public resolver that logs everything. Check leaks three ways: client system logs, gateway monitoring, and synthetic tests that run domain lists comparing response sources. In 2026, passive agents that watch DNS stacks and alert on policy breaches are widely available.

Close leaks with policies and priorities: explicit rules for private zones, disabling automatic public resolvers on clients, and using DoH/DoT to corporate resolvers for anti-interception. Don’t forget guest Wi-Fi, where attackers can spoof DHCP. A client with strict Split DNS knows where domains belong and ignores false routes.

Filtering, RPZ, and Zero Trust

RPZ (Response Policy Zone) is your DNS-level toxin filter. Block phishing, malware, and command-and-control domains early without waiting on antivirus. Combined with Split DNS, it's sharp: internal domains bypass filtering if needed, externals get checked and blocked. Zero Trust adds context—who the user is, their risk profile, and device. The decision can differ for the same domain based on risk signals.

Don’t overdo it. Overaggressive filtering triggers false positives, especially in DevOps and testing environments with dynamic domain names. Best practices include whitelisting critical zones, clear exception workflows lasting 24–72 hours, and rollback monitoring. Filtering should be like a seatbelt—it doesn’t interfere but protects in emergencies.

Privacy and Log Minimization

DNS reveals your online life story. Don’t keep what you don’t need. Minimize personal data: avoid logging full queries when unnecessary, truncate IPs to prefixes, retain aggregate stats only. In 2026, many companies adopt short retention windows of 7–30 days for raw logs and long-term aggregate storage. This suits investigations and trend analysis while enhancing user privacy.

Remember consent and legal rules. Document in your policy which domains are filtered and how long logs are kept. Sounds bureaucratic? Maybe. But it saves headaches during audits and builds trust within your team. When everyone knows the rules, they work calmly and break the system less impulsively.

DNSSEC, DANE, and Email Hygiene

DNSSEC signs responses, guarding against tampering. It’s sometimes overkill for internal zones but standard for public ones. DANE complements this by binding certificates to DNS. With Split DNS, responsibility is shared: fast and flexible inside, strict and signed outside. This lowers MITM risks and automates checks.

Email records SPF, DKIM, and DMARC are a different story. Ensure consistency between internal and external zones. If you have separate domains for internal and external mail systems, Split DNS must guarantee clients and servers see the right records. Otherwise, expect delivery failures, reputational damage, and clogged queues.

Step-by-Step Split DNS Setup for Popular Stacks

Windows Server DNS with VPN IKEv2 or Always On VPN

Start with zones. In Windows DNS, create internal forward lookup zones for private domains. Then set Conditional Forwarders pointing to authoritative servers for neighboring domains if they’re in other segments or clouds. Verify zone replication, set sensible TTLs, and add PTRs where crucial for AD and logs. Next, client policy: push NRPT via Group Policy specifying that *.corp.local and *.svc.company go to DNS servers inside the tunnel.

For IKEv2 or Always On VPN, configure connection profiles with corporate DNS addresses and domain lists. Enable split-domain filtering so clients don’t resolve private names via public resolvers. Test incrementally—start with internal zones, then external, then hybrid cases like external names redirected to internal reverse proxies.

BIND or Unbound with WireGuard and OpenVPN

BIND offers flexibility, Unbound boasts speed and built-in caching. Create a forward zone for private domains, listing authoritative servers. Allow recursion for external domains but route it to your DoH/DoT upstream or local root hints. In WireGuard, add domain lists in the client resolver config or use scripts to update systemd-resolved routing for needed zones. For OpenVPN, push dhcp-option DOMAIN-ROUTE if supported by clients.

Verification is key. Use dig or drill for internal and external names. Compare response times with cache on/off. Monitor resolver load during peak times. Enable logs during rollout, then reduce to moderate verbosity—otherwise, you’ll drown in noise and miss vital signals.

pfSense or OPNsense with DoT/DoH

pfSense and OPNsense come with built-in resolvers and forwarders. Configure Conditional Forwarding in the GUI for private zones and server addresses. Use DoT for external queries to trusted providers, keep internal traffic over UDP or TLS as policy dictates. Enable caching and sensible limits. Configure Health Check so the resolver swiftly switches to backup upstreams, preventing user timeouts.

Important: when using DoH on clients, ensure rules don’t break internal zones. Forced exclusions and strict DNS routing over the tunnel often solve issues. Test from varied networks—home routers, mobile, guest Wi-Fi—to catch odd behaviors before users do.

MikroTik, Conditional Forwarding, and Routes

MikroTik RouterOS can forward and cache efficiently. Create static domain routes for private zones, specify internal resolvers, and enable caching with TTL limits. Add fallback addresses so services keep running if one node fails. For hybrid access, set interface-based rules so internal DNS always goes through the tunnel.

Test changes on small pilot groups. Reality bites: old routers or custom software pop up here and there. Catch incompatibilities early to avoid production headaches. Keep config templates under version control to save hours restoring from accidental rollbacks.

Client Platforms and Policies

Windows 11 and 12: NRPT, Priorities, and DoH

Windows can explicitly route domains via NRPT. Use GPO or MDM to deploy rules: for *.corp.local, *.int.company, and *.svc.cluster.local, send traffic to internal DNS inside the tunnel. Enable Prefer DoH for external resolvers to encrypt outbound queries but exclude internal domains from DoH. Check interface priorities so the VPN interface leads for target zones.

Don’t forget Split DNS in Always On VPN. The client must know which queries go into the tunnel. In 2026, clients handle mixed scenarios better but subtle conflicts still happen. Log extensively during rollout, use test labs, and run checklists before broad deployment.

macOS and iOS: Profiles, Per-App VPN, and NetworkExtension

macOS and iOS use configuration profiles to define domain lists, resolvers, and per-app VPN rules. This flexibility lets you route corporate apps through the tunnel with internal DNS while browsers use external DoH. Sync is crucial: if an app uses its own resolver, ensure its policy aligns with system settings.

In 2026, Apple sped up DNS stacks and improved caching. Remember retry logic: slow resolvers may cause profile switches. Fine-tune timeouts and priorities to prevent false failovers. Also, keep domain lists concise—long, encyclopedic rules tend to be less stable.

Android 14 and 15: Private DNS and MDM

Android supports Private DNS via DoT and partially manages rules via MDM. Use your corporate agent for Split DNS: internal domains to corporate resolvers, others via DoT to trusted providers. Per-app VPN helps split traffic by app, critical for BYOD—so personal apps remain untouched.

Test various vendor devices. Manufacturers often interpret standards creatively. Same policy on paper behaves differently on two models. Pilots, feedback, quick fixes help avoid waves of negative reviews. And yes, explain benefits to users—when people understand, they update profiles willingly and break less stuff.

Linux: systemd-resolved and Domain-Based Routing

systemd-resolved is excellent for Split DNS. Assign resolvers by interface and domain, set priorities, enable cache and negative cache. NetworkManager integration helps: VPN up means rules apply, VPN down removes them. For WireGuard, scripts can add domain routes when interfaces activate.

Consider container and Kubernetes host nuances. Dev clusters or heavy containers may use their own resolvers. Make sure corporate zones don’t vanish into the void. It’s better to explicitly configure rules in container environments than chase odd timeouts resolved only by TTL expiration.

Practical Tips and Checklists

Planning Domains and Reverse Zones

Start with a map. Which zones are internal, which external, who’s authoritative, who handles recursion. Plan reverse zones for key subnets, add PTRs where logs and security require them. Avoid exotic TLDs internally; stick to private zones or subdomains of existing domains. This eases integration and lowers collision risk.

Watch how users type addresses. If they’re used to short names, support search suffixes and good Suffix Search Lists. Don’t overdo it: too many suffixes cause extra queries and delays. Balance with 1–3 suffixes for most cases plus clear rules for when to use fully qualified names.

Performance, Cache, and Limits

Cache is your best friend if TTLs are controlled. For dynamic services, use short TTLs and aggressive edge caching—branch resolvers will offload central servers. Enable anti-storm measures: per-name query limits, retry bans. In 2026, elastic resolvers automatically scale with load and retract capacity overnight.

Profile response times. Normal DNS falls between 20–40 ms for internal zones and 40–120 ms externally. Spikes to 300–500 ms mean digging is needed: cache overload, upstream issues, or DoH/VPN conflicts. Find bottlenecks and maintain SLOs. DNS is part of the SRE story now.

Monitoring, Alerts, and SLO

Set up three monitoring levels: synthetic domain list tests, resolver metrics (QPS, NXDOMAIN, SERVFAIL, cache hits), and trace user sessions for complex incidents. Alerts shouldn’t trigger on every hiccup—let systems tolerate spikes for 10 minutes before waking engineers at night.

Create dashboards: internal zones, external zones, error types, latency percentiles. Watch p95 and p99—they’re more honest than averages. Train your team to read these charts—a good visualization saves hours of meetings. Faster insights, faster fixes, faster business uptime.

Documentation, Training, and Change Management

Write rules simply. Which zone is where, responsibilities, allowed exceptions, and how to document them. Newcomers and cross-team folks should grasp the picture in 10–15 minutes. Possible if you ditch jargon and keep it clear. An internal portal with concise guides works wonders.

Implement change management: small batches, canary deployments, quick rollbacks. Test changes in pilots and record outcomes. Split DNS mistakes aren’t usually fatal but do annoy users. Discipline and incremental updates prevent chaos.

Real-World Cases: What Worked and What Didn’t

A Bank with 30,000 Employees

The bank had three AD zones, two private cloud zones, plus a public storefront domain. Users complained of up to 1.5-second delays logging into client banking and CRM. We deployed Split DNS with forwarding for cloud zones, optimized TTLs to 120 seconds for stable services and 30 seconds for Kubernetes, and added RPZ for phishing. Result: p95 resolution dropped from 420 ms to 110 ms, login felt instantaneous.

What didn’t work right away? Overaggressive DoH on clients intercepted internal domains via the public resolver. Fixed with exclusion policies, and things stabilized. Lesson: don’t trust default settings, especially on diverse device fleets.

Multi-Cloud Startup with Fast Releases

The startup ran prod on AWS and test on GCP, with CICD hopping zones every few weeks. They managed this via Split DNS with dynamic forward zones automated from Git. Developers got new records within a minute; users always resolved the correct addresses. Edge cache saved bandwidth.

Once, they caught a quirky CDN/ECS bug: geo-cache selected wrong nodes due to EDNS extension. They limited ECS for some domains. Sometimes fine-tuning is magic. Delivery improved by 12–18% on p95.

Manufacturing and Branch Networks

Factories, machines, SCADA, and legacy controllers—Split DNS prevented chaos. Private factory systems resolved locally and predictably. Lightweight caching resolvers on each branch forward to the hub with strict TTLs. When links went down, production kept going because cache held critical records.

Challenges were old printers, unexpected recursors, and smart switches with their DHCP. We disabled external leases, tightened controls, and added monitoring portals to track query sources. After a week of cleanup, the network calmed and issues became rare.

Government Sector and Compliance

Privacy is especially strict here. Zones were separated, DNSSEC deployed on public domains, logging of personal data limited, and log retention defined clearly. External queries used DoH to trusted resolvers; internals stayed inside VPN. The audit team was pleased, users noticed nothing—and that’s the best compliment.

The key is documentation and repeatability. Without clear rules, audits are painful dramas. Split DNS shows transparency: here are the policies, monitoring, logs, and exceptions. Calm, human, no mysteries.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Duplicate Records and Split-Horizon Pitfalls

The sneakiest error is keeping duplicate records in different places. They might match today, diverge tomorrow, and confuse users the next day. Solution: use forward or stub zones instead of copies. One source is authoritative; others just route queries. Easier to manage and explain why answers differ.

Split-horizon itself isn’t evil but demands discipline. If responses differ for internal and external clients, synchronize TTLs and update both sides together. Otherwise, mobile users might see one thing; office users another—very confusing.

Wrong Resolver Order on Clients

Another trap: client queries public resolvers first, then corporate ones, causing internal names to appear "not found." Fix with interface priorities, NRPT rules, and explicit domain routes. Test each platform carefully—don’t assume defaults are smart.

Add simple diagnostics for support: a 5–7 step checklist to trace where queries go. This slashes troubleshooting time and keeps engineers from dealing with basic questions repeatedly.

EDNS, ECS, and CDN Surprises

EDNS and ECS affect CDN cache geo-selection. Sometimes users don’t get closest nodes. Check if your resolver passes ECS info and how. For some domains, restricting ECS improves stability. The result? Lower latency, fewer spikes, and fewer complaints.

Don’t be afraid to experiment with a small user group. Measure before wide rollout. CDNs love tweaking their setups, and your fine-tuning can add 10–20% speed gains if aligned well.

Certificates, PTR, and Reverse Zones

SSL and mutual TLS hate DNS messiness. If CN and SAN point to domains resolving incorrectly, handshake errors occur. Clean up: internal names resolve via internal resolvers only; external names externally. Maintain PTRs for key systems or diagnostics and SIEM become cryptic puzzles.

Reverse zones are often neglected. Later, teams wonder why analytics fail or audits mark all as "unknown guests." Add PTRs where needed and apply sensible TTLs. Small effort, big sanity saver.

2026 Trends and What to Adopt Now

ZTNA and Software-Defined Perimeter

Zero Trust and SDP reshape access architectures. Split DNS becomes part of context-aware policy: the resolver sees user, device, app, risk, then decides where to route queries and what answers to give. We’re moving from simple “where to query” to smart “why and whom to answer.”

Practically, this means an agent on the device, cloud policies, managed resolvers with filtering, and dynamic routing through ZTNA gateways. The idea is simple; execution is complex. But control and security gains are huge. Start small and grow with your team.

DNS-over-QUIC and Encrypted ClientHello

QUIC speeds up and stabilizes connections even in packet loss scenarios. DNS-over-QUIC is a natural evolution, with growing client and resolver support in 2026. Encrypted ClientHello hides TLS handshake details, adding privacy benefits for Split DNS by masking metadata from the network edge and making surveillance harder.

The catch? Compatibility and diagnostics. Test thoroughly—enabling QUIC might disrupt older proxies or IDS. But the trend is clear: in a year or two, this will be the dominant encryption method for many scenarios.

Managed Resolvers with AI Suggestions

Managed resolvers in 2026 offer features like auto-tuning TTLs, adaptive caching, alerts on problematic zones, and anomaly detection using machine learning. They spot when a domain slows down and suggest lowering TTL or switching upstream. Or note when a user subnet overloads cache and advise moving resources.

Not magic, but close. Key is staying in control—any auto-fixes go through Change Review, even if expedited. Resolver mistakes cause hours of chaos. Yes, speed is desired but surprises aren’t. Smart tips yes; fully autonomous fixes cautiously.

Regulations, Compliance, and Data

Privacy demands are rising. Companies revise log policies, introduce pseudonymization, and separate operational metrics from personal data. Split DNS supports this by limiting "extra eyes" and directing sensitive queries only to trusted resolvers. Logs get cleaner, leak risk shrinks, and audits ease.

Daily advice: document which domain categories go where, who sees what, and what logs record. It’s dull but priceless during incidents. You quickly answer key questions instead of hunting chaos.

FAQ: The Essentials

What Is Split DNS in Simple Terms?

It means different domains get resolved by different DNS servers based on rules. Internal names go to corporate resolvers via VPN; external ones go to public or managed resolvers. Users simply see "everything works," while you control privacy, speed, and security.

How Does Split DNS Differ from Split Tunneling?

Split DNS only separates DNS resolution. Split Tunneling splits all network traffic. They can be used alone or together. For example, keep a full tunnel for all traffic but resolve external domains via DoH and internal ones via corporate DNS.

How Do I Know If I Have a DNS Leak?

Signs include internal names failing to resolve, odd responses, or slow AD or portal logins. Check resolver logs, run synthetic tests, and see which resolver answers private zones. If it’s not your corporate DNS—you have a leak.

Should I Enable DoH or DoT If I Already Have VPN?

Sometimes yes. DoH/DoT protect queries from tampering and spying before the tunnel or after exiting it if using an external resolver. But set exceptions for internal zones so private service access isn’t broken. Balancing security and compatibility is key.

Can Split DNS Be Set Up Without Client Device Rights?

Partially. You can configure resolvers on the network edge and enforce forwarding. But the best approach is centralized client policies via MDM or group policies, making rules uniform and minimizing unexpected bypasses.

What Are the Most Common Mistakes?

Duplicate zones instead of forwarding, wrong resolver priority on clients, overlong TTLs, DoH conflicts with internal zones, and insufficient monitoring. Fix these with discipline, pilots, checklists, and sensible defaults. And don’t hesitate to simplify where possible.